First principle of British foreign policy: Protecting England by the finances of India (From the Archives)

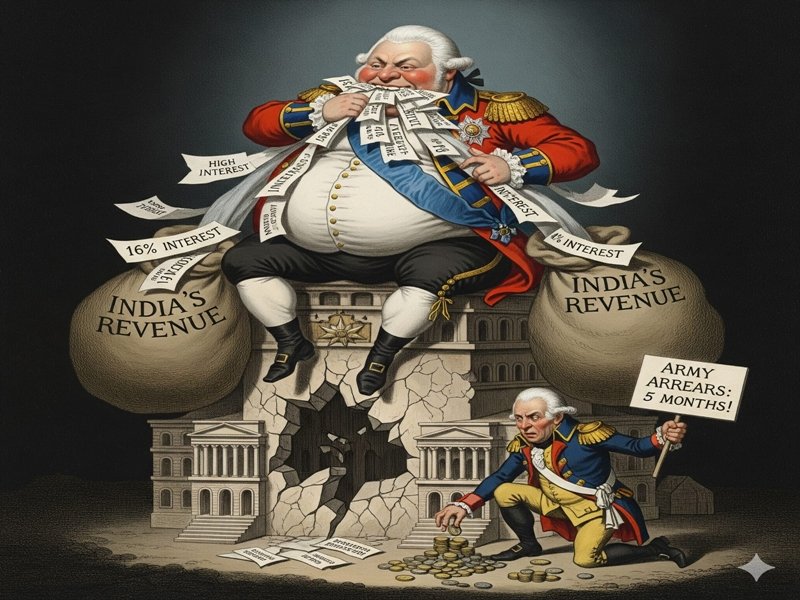

New Delhi, Nov 30 (LatestNewsX) – In the early 19th‑century heartland of India, people were not battling rival rulers or foreign armies; they were fighting a stealthy, all‑encompassing debt engineered by the British East India Company (EIC) under Governor‑General Marquis Wellesley. This financial load became the most devastating force unleashed on the subcontinent.

Wellesley’s triumph over the Maratha Confederacy and the annexation of affluent states such as Oudh were not paid from the EIC’s vast reserves but from crippling, high‑interest loans borrowed in India. Consequently, the Indian debt swelled from about £11 million sterling to over £31 million.

The crisis finally reached London, provoking swift panic and a stark revelation. Parliamentary debates of 1805‑06 exposed the true heart of Britain’s foreign policy toward India: protecting the British Exchequer from the fallout of its own imperial ambition mattered more than India’s welfare.

The dire situation was vocally described by men like Francis, who asserted that his sole remaining duty was to “protect England not against the company, but against India and its government.” His chilling declaration confirmed Indians’ fears that the colony had become a source of danger for “the mother country” itself.

I. Wellesley’s Excess and the Debt Machine

The enormous debt threatening the EIC’s survival stemmed from a governance model that prized “despotic power” and “flagitious profusion.” Wellesley’s administration abandoned the Company’s pledge for prudence, replacing it with lavish displays of monarchical grandeur.

He labelled expenditures such as the Calcutta Palace—costing £220,000 and unmatched even by Eastern princes—as “wasteful, profuse, unauthorized, extravagant expenditure of the public money.” Though laws forbade accepting money from local subjects, he allegedly received £120,000 for “luxuries of the table, and other purposes of his own private gratification.”

Personal extravagance and relentless military campaigns ensured that revenue from conquered provinces was channeled straight into interest payments. The high‑interest loans (nominally 10–12 %, effectively up to 16 %) created a debt engine that drained Britain’s credit. The narrative Mr. Francis offered was clear: “commerce produced factories, factories produced garrisons, garrisons produced armies, armies produced conquests, and conquests had brought us into our present situation,” painting a picture of a self‑reinforcing cycle of ruin.

II. Cornwallis’s Disenchantment

The real extent of the financial disaster unfolded in 1805 when Lord Cornwallis returned to India to reverse Wellesley’s sprawling policies. By then, the Empire’s finances were in a “deplorable statement,” as Parliament was immediately warned.

The army was “little short of five months” behind in pay, and irregular troops cost nearly £60,000 sterling per month. Cornwallis deemed this cost “much more injurious to the company than their hostility in the field could possibly be.” To cover arrears, he resorted to emergency, illegal measures, detaining company treasure destined for China—amounting to £250,000—and forcing the Madras government to spare £50,000 of its own specie.

These actions damaged the company’s very raison d’être: a lucrative China trade. The emergency seizure of treasure forced the Governor‑General to compromise the company’s commercial interests to keep the army operational. The war’s expenses had, in fact, already caused great harm to the colony.

III. The Annual Half‑Million “Promise”

The EIC’s failure was magnified by its legal commitments to the British public. When its charter was renewed in 1793, the company was required to send £500,000 per year from its trade profits to the British Treasury, with its assets in England liable for payment. This sum served as a symbolic price for retaining its monopoly and proving that India was not a drain but a contributor.

Although the law allowed deferral during wartime, the parliamentary inquiries exposed that the company had “never paid any part” of the stipulated sum. While the company could argue that the European war had removed surplus profits, the rise in Indian debt indicated that India was no longer a source of profit; it was becoming a financial liability poised to drag Britain down.

IV. Protecting England from Its Own Empire

The financial exposure forced a shift in policy rhetoric. Francis, once a defender of Indian princes, now saw his task as defensive. He declared: “The only duly that is new left to me… is to protect England not against the company, but against India and its government.” This was not a abandonment of Indians but a realistic acknowledgement that “flagitious profusion” and “ruinous conquests” could only be stopped by preventing chaos from spilling into Britain.

Francis warned that the evils originating in India would “not confine themselves to that country.” He predicted that India, under current management, would provide “no revenue” and instead consume British resources and “the flower of our troops” in “ruinous conquests.” With the company’s insolvency near, he argued that Parliament would soon have to “protect the finances of this country against the distresses of India.”

By presenting the issue as a threat to British fiscal stability, Francis sought to change governing principles, calling for a policy built on “jealousy, justice, and moderation” in India—essentially a defensive foreign policy not against the Marathas or the French, but against the country’s own financial self‑destruction.

V. Lord Castlereagh’s Guaranteed Loan

The British government, fully aware of the huge debt threatening the EIC’s trade and future obligations, explored a solution that would stabilize India without re‑applying fiscal pressure. The plan focused on converting the costly Indian debt into cheaper European debt.

Lord Castlereagh, initially skeptical about the Company’s state, eventually admitted that something needed to be done. He proposed raising a massive loan under parliamentary sanction, shifting a substantial portion of the Indian debt—estimated at around £16 million—to the lower‑interest English market. He argued that a parliamentary‑guaranteed loan would be more advantageous than one the company would seek alone.

This strategy mirrored earlier Irish loans: the public would guarantee the loan, and the EIC’s Indian revenues would be mortgaged to repay it. Castlereagh emphasized that:

- Converting debts at 10–12 % to lower European rates would save roughly £800,000 yearly.

- That saving would support the government’s rightful £500,000 annual share.

- The loan, secured on territorial revenues set apart for military costs, carried risks no greater than the precedent set by the Irish rounds.

The proposal was not a humanitarian relief for India but a financial maneuver to stabilize a colonial economy sinking under imperial overreach. It ensured Britain’s national treasury would reap long‑delayed profits while preventing the empire’s debt from contaminating the mother country.

Conclusion

A parliamentary analysis of India’s finances screams a stark, unromantic view of colonialism. Wellesley’s “schemes of conquest and extension of dominion” produced vast territorial gains but left India with an overwhelming debt teetering on collapse.

Castlereagh’s government‑backed loan was not generosity but a strategic act of self‑preservation—preventing the British state from being contaminated by a failing colonial project. Francis’s fears that Britain would have to “protect the finances of this country against the distresses of India” came to pass.

For Indians, the embarrassment was that the solution did not reverse the debt, only converted it. The crown‑guaranteed loans ensured the burden would be permanent, tied to the colony’s entire revenue. High‑interest Indian paper was swapped for cheaper European bills, cementing the economic shift of wealth from Hindustan to the metropolis.

Thus, the EIC’s territorial conquest ended with an iron‑clad financial chain. “The First Principle of Foreign Policy” succeeded: India was neutralised as a threat to Britain’s prosperity not by battlefield victories but by transferring its unsustainable debts onto the sovereign credit of the crown, safeguarding the empire’s financial integrity at the cost of India’s long‑term economic future. Clearly, while the conqueror’s glory may fade, the banker’s lien endures forever.

Stay informed on all the latest news, real-time breaking news updates, and follow all the important headlines in world News on Latest NewsX. Follow us on social media Facebook, Twitter(X), Gettr and subscribe our Youtube Channel.